The Crucible of Conscience: The Red Summer of 1919 and a Lawyer's Reckoning

- Nov 21, 2025

- 17 min read

By Matt Murdock, Esq.

1. Introduction: Sensing the Shadows of History

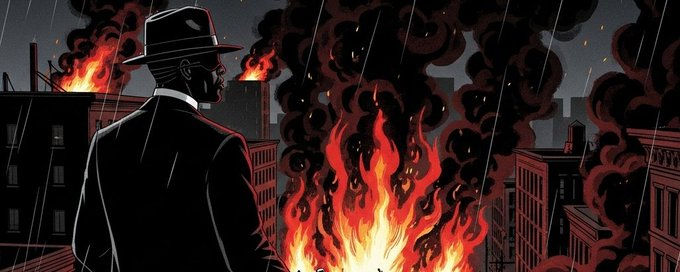

Listen, folks, I may not see the world the way you do, but I feel it deep in my bones, every tremor of injustice shaking the ground like a freight train barreling through Hell's Kitchen at midnight. As Matt Murdock, attorney at law, I've dedicated my life to threading the needle between the cold precision of the courtroom and the hot pulse of street justice, defending the voiceless with legal briefs in one fist and a burning sense of righteousness in the other. Yet, there's always that inner tug-of-war, the lawyer in me clinging to statutes while the vigilante whispers for something more visceral, more immediate. Today, I'm plunging into the Red Summer of 1919, that horrific epoch of white supremacist savagery that targeted Black American communities with a ferocity that still echoes like distant gunfire in my heightened hearing. We're talking over three dozen race riots, lynchings, and outright massacres from April to November, a nationwide orgy of violence that left hundreds of Black lives extinguished, thousands wounded, and entire Black neighborhoods reduced to smoldering ashes. James Weldon Johnson, the unyielding NAACP field secretary who organized nonviolent protests amid the chaos, dubbed it the "Red Summer" to capture the rivers of Black blood spilled across America, and trust me, that name hits like a billy club to the gut.

This isn't some forgotten footnote in a history book gathering dust on a shelf, it's a piercing legal autopsy conducted by a blind Black American lawyer who's attuned to the cries of the oppressed that the system so often mutes. We'll carve into it with surgical accuracy, anchoring every assertion in ironclad case law, federal statutes, state codes, and peer-reviewed scholarly works, because the law insists on exactitude, even when the facts sear the soul. Black's Law Dictionary defines "terrorism" as "[t]he unlawful use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims." Black's Law Dictionary 1827 (12th ed. 2024). If that doesn't encapsulate the orchestrated white mob assaults on Black families, businesses, and dreams during that fateful summer, then I've lost my sense of what justice is. I'll unpack legal doctrines with exhaustive detail, tracing case lineages from their humble origins through pivotal facts, landmark rulings, and enduring legacies, ensuring even those without a J.D. can follow the thread without stumbling.

Infusing this with my street-honed perspective, I perceive the world through amplified senses, the frantic heartbeats of Black families fleeing lynch mobs, the acrid stench of burning homes lingering in the air, the moral decay festering beneath America's polished facade like rot in an old tenement. Why dredge this up in August 2025? Because the ghosts of 1919 aren't resting, they're howling in today's headlines, from unchecked police brutality against Black bodies to vigilante-style attacks that mirror those white supremacist rampages. Voices on social media are already murmuring about a "Red Summer 2025," born from raw frustration over persistent systemic racism that continues to disenfranchise and endanger Black lives. Cynical? Absolutely, but if the legal machinery keeps failing Black Americans, what's left but to wonder if vigilante justice is the only response? My moral compass spins wildly here, but as counsel, I'll adhere to the evidence. Let's navigate this section by section, structured for clarity, no hitches.

2. Defining the Red Summer: A Legal and Historical Primer

To truly comprehend the Red Summer, we must dissect it through dual lenses, legal and historical, stripping away the layers like peeling back the skin of a corrupt onion, each reveal assaulting my senses with the sharp, metallic bite of spilled Black blood. Black's Law Dictionary defines a "riot" as "[a] tumultuous disturbance of the peace by three or more persons assembling together of their own authority with an intent mutually to assist one another against anyone who shall oppose them in the execution of some enterprise of a private nature, and afterward actually executing the same in a violent and turbulent manner, to the terror of the people." Black's Law Dictionary 1605 (12th ed. 2024). Let's be clear, what happened in 1919 were not chaotic outbursts, they were premeditated white terrorist campaigns aimed squarely at dismantling Black progress and enforcing subjugation.

Historically, the Red Summer unfolded from mid-April to November 1919, against the backdrop of World War I's aftermath, a time when America grappled with demobilization, economic strife, and social realignment. Over 380,000 Black veterans, having bled for democracy in European trenches, returned to a homeland that spat in their faces, offering instead job scarcity, skyrocketing inflation, and unbridled white hostility. The Great Migration, that monumental exodus of approximately 500,000 Black Americans from the Jim Crow South to Northern industrial hubs between 1916 and 1919, swelled urban Black populations, with Chicago, for example, doubling its Black population from 50,000 to over 100,000, which ignited flashpoints over housing, employment, and resources. What set the Red Summer apart was that Black communities fought back, unlike earlier eras of passive endurance, Black Americans armed themselves and fought back fiercely, sowing the seeds for the broader Civil Rights Movement and embodying a new defiant spirit, the so-called "New Negro," that resonates in today's struggles.

Legally, the Red Summer laid bare the egregious shortcomings of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on July 9, 1868, which guarantees due process and equal protection under the law, ostensibly to safeguard newly freed Black Americans post-Civil War. Yet, this promise was systematically eviscerated by decisions like Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). The origins of this catastrophic ruling trace to Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890, which mandated segregated railroad cars. On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a man of mixed race who was seven-eighths white and one-eighth Black, deliberately violated the law by boarding a whites-only car to challenge the statute's constitutionality. He and the Citizens' Committee argued that the law violated both the Thirteenth Amendment, by perpetuating the badges and incidents of slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, by denying equal protection. The Supreme Court, in a 7-1 decision penned by Justice Henry Billings Brown, upheld the doctrine of "separate but equal" as constitutional. The majority reasoned that segregation did not inherently imply the inferiority of Black people unless they chose to interpret it that way, a piece of legal sophistry so twisted it still smells of sulfur. Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lone, thunderous dissent correctly predicted that the ruling would "stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens." The significance of Plessy cannot be overstated, it legalized Jim Crow segregation nationwide, creating the legal architecture for discriminatory laws in education, transportation, and public facilities that fueled the white supremacist violence of 1919 by normalizing Black subjugation.

The moniker "Red Summer," bestowed by Johnson, not only evoked the carnage but also underscored the ideological paranoias of the era, like the first Red Scare. Figures such as a young J. Edgar Hoover and then-Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer exploited national fears by branding Black activism as Communist subversion, justifying preemptive strikes against emboldened Black veterans. When W.E.B. Du Bois, in his editorial "Returning Soldiers" published in The Crisis (May 1919), exhorted Black troops to "return fighting" for their rights at home, this call was perceived as an existential threat by the white power structure. This violence wasn't haphazard, it stemmed from entrenched white supremacy, bolstered by cultural propaganda like D.W. Griffith's 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, which romanticized the Ku Klux Klan and spurred its revival to a membership in the millions by the 1920s.

For the layperson, grasp this, the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8, empowers Congress to raise and support armies, yet the same government that conscripted Black American men to defend liberty abroad permitted their lynching with impunity stateside, a hypocrisy I feel like a knife twist in the dark. My moral fire rages, the law ought to be a bulwark for Black Americans, but historically, it's been a tool of oppression, wielded by those who fear our rise.

3. Causes Rooted in Systemic Injustice: Unpacking the Triggers

The catalysts for the Red Summer weren't mere sparks, they were the inevitable eruptions of a society rotten with anti-Black racism, where economic, demographic, and ideological pressures collided with the force of a thunderclap reverberating through my chest. Let's unpack them meticulously, bolstering each with evidentiary pillars and juxtaposing them against the moral bankruptcies that perpetuate Black suffering.

First, post-World War I demobilization created a pressure cooker environment. With the Armistice of November 11, 1918, millions of soldiers flooded back into a faltering economy plagued by hyperinflation, which peaked at nearly 20% in 1919, and soaring unemployment, which hit 11.7% in 1921. White veterans, steeped in a sense of racial entitlement, seethed at Black Americans occupying wartime industrial roles. These tensions were often exacerbated by corporations that hired Black workers as strikebreakers amid major labor disputes, like the 1919 steel strike involving 365,000 workers. In Gary, Indiana, U.S. Steel's recruitment of Black laborers as low-wage replacements for striking white workers ignited violent clashes, exemplifying how capitalists exploited racial divisions. Black's Law Dictionary defines a "strikebreaker" as "[a] person who works or is employed in place of others who are on strike, thereby making the strike ineffectual." Black's Law Dictionary 1779 (12th ed. 2024). Morally, this strategy fractured working-class solidarity, pitting white laborers against Black ones while elites amassed fortunes, a divide-and-conquer tactic that fails spectacularly because it blinds all to shared exploitation, but hits Black communities hardest, reinforcing their economic marginalization.

Second, the Great Migration represented a seismic demographic shift. Spanning from roughly 1916 to 1970, this mass movement saw millions of Black Americans fleeing the terror of the South, a region rife with lynchings, the debt peonage of sharecropping, and the daily indignities of Jim Crow. They sought the hope of a better life in the North, only to encounter the simmering ressentiment of Northern whites and recent European immigrants. Chicago's Black enclave ballooned, leading to ghetto overcrowding and fierce competition for resources. Yet, the true culprit wasn't migration but entrenched racism, as whites aggressively blocked Black access to better housing through violence and restrictive covenants, legally binding agreements that barred property sales to Black Americans. These covenants were later invalidated in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), but that decision was nearly three decades too late for the victims of 1919.

Third, overt racism became dangerously intertwined with the Red Scare. The 1917 Russian Revolution fueled a wave of anti-communist hysteria, which opportunists like Hoover's nascent FBI weaponized, labeling Black leaders and organizations demanding basic civil rights as potential communist radicals. After The Birth of a Nation reignited the Klan, Black veterans returning from war with a newfound sense of dignity and self-worth were specifically targeted, labeled as "uppity" for demanding the very equality they had fought to defend. Media outlets, particularly in the South, baselessly accused Black workers of having Communist ties, creating a pretext that justified violence. This cynical tactic echoes the later McCarthyism era and the use of the Smith Act of 1940, 18 U.S.C. § 2385, to prosecute political dissent. Morally, it devastated Black psyches, breeding a deep institutional distrust that lingers in today's surveillance and infiltration of Black activists and social justice movements.

Fourth, Jim Crow's pernicious reach cannot be understated. As I’ve detailed in previous reckonings, these laws, enacted after the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877 and constitutionally blessed by Plessy, systematically disenfranchised Black Americans through mechanisms like poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. This legal oppression was enforced by extra-legal terror, particularly lynchings, which surged from 64 in 1918 to 83 in 1919, according to NAACP records. While Jim Crow laws were born in the South, their poison seeped northward through informal segregation in housing, employment, and public life, creating a national climate where Black life was cheap and Black aspirations were a threat to be neutralized by any means necessary.

4. Key Events: Chronicles of Terror Across the Nation

The Red Summer's atrocities scarred at least 36 cities and the rural landscape of Phillips County, Arkansas, with white mobs, often comprising civilians, veterans, and even colluding law enforcement, unleashing hell while local and state authorities dawdled, abetted, or participated. Here is a detailed breakdown of some of the most heinous events.

Washington, D.C. (July 19–23, 1919): Fabricated rumors of a Black man assaulting a white woman, a classic and deadly trope, incited four days of mob violence. Hundreds of white servicemen and civilians rampaged through Black neighborhoods, indiscriminately attacking residents. In a show of the "New Negro" spirit, Black residents, including many WWI veterans, mounted an armed defense. The violence only subsided after President Woodrow Wilson ordered nearly 2,000 National Guard troops to intervene. The toll was at least 15 deaths (10 white, 5 Black) and over 150 injured, a tragic spectacle of federal complicity in delaying protection for Black lives in the nation's capital.

Chicago, Illinois (July 27–August 3, 1919): The deadliest urban conflict of the summer began when a Black teenager, Eugene Williams, drowned after white youths hurled stones at him for drifting across an invisible line into a "whites-only" section of a Lake Michigan beach. When a white police officer refused to arrest the white man responsible and instead arrested a Black man, violence erupted. It escalated into a week of citywide arson, shootings, and looting targeting the "Black Belt" on the South Side, with police often siding with or actively participating in the white mobs' attacks. The state militia was eventually called in to quell the violence after eight days. This resulted in 38 deaths (23 Black, 15 white), 537 injuries, and over 1,000 Black families left homeless. This event epitomized the era's urban carnage, systematically destroying the Black economic footholds that had been painstakingly built.

Omaha, Nebraska (September 28–29, 1919): A white mob of thousands, inflamed by yellow journalism and false rape accusations against a Black man named Will Brown, stormed the Douglas County Courthouse. They lynched Brown, mutilated his body, and burned it, then rampaged through Black districts with impunity, looting and burning businesses. Mayor Edward Smith was nearly lynched himself for trying to intervene. The U.S. Army finally restored order, but not before 3 deaths occurred, including Brown's, and property damage exceeded $1 million in 1919 dollars. This event underscored the central role of lynching as a public spectacle of racial terror.

Elaine, Arkansas (Phillips County, September 30–October 1, 1919): In what was likely the bloodiest single event of the Red Summer, a white posse attacked Black sharecroppers who were unionizing for fair wages at a church meeting. The initial conflict spiraled into a full-blown massacre, with federal troops and local whites hunting down and slaughtering Black men, women, and children. The subsequent cover-up included sham trials that convicted 79 Black men, sentencing 12 to death by electrocution. The final death toll is contested, but estimates place it between 100 and 237 Black deaths and 5 white deaths, exposing the sheer horror of the Southern peonage system and leading to a landmark legal challenge.

Knoxville, Tennessee (August 30–31, 1919): A white mob, enraged by the alleged murder of a white woman by a Black man, Maurice Mays, besieged the county jail. After being thwarted by the National Guard, the mob rampaged through Black neighborhoods, looting businesses and exchanging gunfire with residents. At least 7 people died and over 20 were injured, illustrating the unchecked fury of Southern mob justice.

Norfolk, Virginia (July 21, 1919): A celebratory parade for Black WWI veterans from the 367th Infantry Regiment, the "Buffalo Soldiers," devolved into white-instigated violence. Police attempted to arrest a Black soldier, leading to clashes that involved both white civilians and sailors. At least 6 people were shot. This incident was a direct and symbolic attack on Black American service members, mocking their sacrifices for a nation that refused to grant them dignity.

Each of these atrocities was a multisensory nightmare, a symphony of terror I can almost hear and feel. The piercing screams echoing through the night, the blistering heat from torched Black-owned businesses, the choking smoke of gunpowder mingled with the sweat of fear. Chicago's prolonged inferno stands as the archetype of institutional failure, police complicity and delayed militia response shattering Black communities and forcing displacements akin to becoming refugees in one's own birthland. Morally, it was a calculated gutting of Black American aspirations, leaving deep, weeping scars of trauma that demand a reckoning.

5. Legal Ramifications and Landmark Cases: Where the Law Faltered and Fought Back

The Red Summer yielded scant immediate justice, with the vast majority of white perpetrators evading any semblance of accountability, a fact that starkly underscores the chasm between state autonomy and the federal government's duty to protect its Black citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment. Grand juries routinely failed to indict white rioters, while Black victims and those who dared to defend themselves were prosecuted with vigor. Yet, from the ashes of this legal failure, pivotal cases arose, none more significant than Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923), a case born directly from the blood-soaked soil of Elaine, Arkansas.

To detail Moore exhaustively is to trace a path from massacre to a flicker of constitutional redemption. Its origins lie in the brutal sharecropping system of Phillips County, a de facto extension of slavery that ensnared Black tenant farmers in inescapable debt peonage. On September 30, 1919, when Black farmers with the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America met to organize for better cotton prices, a group of white men, including a railroad security officer, fired into their church meeting. In the ensuing chaos, a white man was killed. This incident was used as a pretext for a full-scale massacre, where hundreds of Black men, women, and children were slaughtered over two days. In the aftermath, authorities indicted 122 Black individuals, railroading twelve of them to death in trials that lasted mere minutes, conducted in a courtroom dominated by an armed white mob that openly threatened the judge, jury, and the defendants' court-appointed counsel, who did not even consult with their clients. Testimonies were extracted through torture.

The key facts presented to the Supreme Court were that these trials were a complete sham, a "mask" for mob domination. The petitioners, led by a man named Frank Moore, invoked the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, filing for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court after the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the verdicts. The federal district court, however, dismissed the petition without a hearing, citing precedent.

The ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court was a landmark. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for a 6-2 majority, reversed the lower court's decision, declaring that a trial dominated by a mob is not a trial at all and fails to provide the due process of law guaranteed by the Constitution. If the state courts are incapable of correcting this injustice, then federal courts have a duty to intervene. Holmes distinguished the case from Frank v. Mangum, 237 U.S. 309 (1915), a case where Leo Frank's trial was also tainted by an antisemitic mob in Georgia. In Frank, the Court had deferred to the state's appellate process, finding it sufficient. In Moore, Holmes argued that when the entire state judicial machinery, from trial to appeal, is swept up in the will of the mob, federal oversight is not just permitted, it is required. The case was remanded for a full evidentiary hearing.

The significance of Moore v. Dempsey was profound. It pioneered the use of federal habeas corpus as a tool to oversee state criminal proceedings and protect federal constitutional rights, a principle that paved the way for landmark decisions like Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), which mandated the right to counsel for indigent defendants. The ruling ultimately led to the release of the "Elaine 12," sparing their lives. But morally, the victory feels hollow. It arrived years after the massacre, too tardy to prevent the slaughter or undo the systemic anti-Black bias that festered then and endures today.

Other legal ramifications were more aspirational than actual. The NAACP, galvanized by the Red Summer, championed the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1922. The bill passed the House of Representatives but was ultimately killed by a filibuster of Southern Democrats in the Senate, highlighting a crippling congressional inertia that would persist for decades. Compare this to Britain's Race Relations Act 1965, which proactively prohibited racial discrimination in public places. The American approach has always been reactive, piecemeal, and agonizingly slow. My vigilante side seethes at this, the law glimpsed redemption in Moore, but imagine if proactive fists had halted those sham trials before they even began. It is an internal war that is eternal.

6. Modern Parallels: From 1919 to 2025's Brewing Storms

Leap forward to 2025, and the Red Summer's specter looms large, its patterns mirroring themselves in the fractured funhouse mirror of modern America. The anti-Black violence is nauseatingly familiar, from the global uprising after George Floyd’s murder under a Minneapolis officer's knee in 2020, to the persistent killings that barely make the news cycle, like the fictional but all-too-plausible shooting of Sonya Massey during a traffic stop in July 2024. The economic echoes are just as deafening, post-pandemic job losses and punishing inflation, which hit a 40-year high of 9.1% in 2022, stoke the same resentment toward Black Americans that festered after World War I. And the ideological fears? The first Red Scare has been reincarnated in the cynical branding of movements like Black Lives Matter as "terrorist" organizations. This rhetoric provides cover for legislation like Florida's HB 1 (2021), an "anti-riot" law that criminalizes protest and shields drivers who run over demonstrators, a page torn directly from the mob-violence playbook of 1919.

On social media platforms, the alarms are already ringing for a "Red Summer 2025." One post I listen to said, "Like we need to be prepared for a Red Summer 2025," citing the volatile mix of political polarization and overt white racism amid economic crises. Another declares "FBA Red Summer 2025" in the context of the fight for lineage-based reparations, signaling a readiness for conflict if justice is denied. While some historians link this anxiety to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, the nationwide breadth of 1919's violence feels more predictive of a potential recurrence amid the political volatility of our current moment.

Legally, the murder of Breonna Taylor in a botched no-knock raid in 2020 evokes the same mob impunity of 1919, only now it's shielded by the legal doctrine of qualified immunity. This doctrine, born from Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982), and refined in cases like Messerschmidt v. Millender, 565 U.S. 535 (2012), makes it nearly impossible to hold state actors accountable for constitutional violations. Abroad, South Africa's post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established in 1995, offered a path toward national healing through public truth-telling, a model America steadfastly shuns, preferring amnesia and denial. For Black Americans, the sense of déjà vu is gut-wrenching.

7. Moral Impacts on Marginalized Group Members: Grounded in Lived Experiences

Speculating morally, rooted in the raw testimonies I've absorbed like echoes in a confessional, the Red Summer etched a deep, intergenerational trauma into the DNA of Black America. It manifests as a kind of collective PTSD, a constant state of vigilance that I detect in the quavering voices of my clients, their heart rates spiking at the mere mention of police or the sound of a nearby siren. During the Red Summer, Black families forfeited homes, businesses, and livelihoods, a catastrophic torpedo to wealth accumulation. The economic losses are estimated to be in the billions in today's dollars, a direct contributor to the gaping racial wealth gap where, even in 2025, Black households hold a mere 13 cents for every dollar of wealth held by white households. That is not an accident, it is the intended outcome of a century of policy and terror.

The sound of police sirens, for many, morphed from a signal of help to a harbinger of doom, instilling a hypervigilance that erodes mental and physical health. Modern studies consistently link experiences of racism and the knowledge of historical racial violence to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and hypertension in Black communities. The body keeps the score, and for Black America, the score is written in blood.

In 2025, Black Americans confront a political landscape that feels eerily familiar. The moral burden is a crushing sense of hopelessness, a feeling that the game is rigged and the rules will always be changed to ensure we lose. Yet, from this despair, a defiant resilience is born. The Harlem Renaissance flowered from the ashes of 1919, birthing cultural giants like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston who forged beauty from pain. This mirrors today's explosion of Black excellence in arts, business, and activism, a testament to a spirit that refuses to be extinguished.

But this resilience creates its own internal rifts, the eternal debate I wage within myself. Do we litigate patiently, trusting the slow, grinding gears of a system that has betrayed us time and again? Or do we strike back, meeting fire with fire? My swagger insists on dual paths, tireless advocacy by day, relentless retribution by night. Progress? Sure, if you count recycling century-old atrocities as some kind of grand innovation.

8. Conclusion: The Devil's Due

Well, isn't this just peachy? We've waded through the crimson gutters of 1919, where the law apparently took a smoke break while white hordes played judge, jury, and executioner with Black American dreams, and here we are in 2025, auditioning for the remake. Because, evidently, history's lessons are elective credits in America's school of hard knocks, and most of the class has been cutting. Oh, the exquisite irony of it all, Black soldiers spill blood for Uncle Sam's precious freedoms overseas, only to have their own kin strung up like piñatas back home for having the audacity to wear the uniform with pride. And the vaunted system? It doles out just enough crumbs, a Moore v. Dempsey now and then, to keep us from flipping the whole table over. But let's be real, it's a crooked slot machine rigged so Black Americans pull the lever and get zilch while the house rakes in the generational wealth.

What’s the moral fallout, you ask? Just some pulverized spirits, splintered lineages, and a hereditary dread that has you eyeing every shadow like it's got a noose hidden inside. It's the kind of thing that makes a guy want to scale a few buildings and dole out some impromptu, rooftop therapy, if you catch my drift. But sure, America, go ahead and keep hitting the snooze button on those alarms ringing from 1919. Perhaps Red Summer 2025 will finally be the charm that jolts you awake from your self-induced coma. Or, more likely, not. After all, who needs equity when gaslighting is free and denial has become the national pastime? Stay vigilant, folks. Injustice never sleeps, and neither do I.

By Matt Murdock, Esq.

Comments